One of the best things about having your own blog is that you can write whatever you want. Even if it is pseudo academic, or as one of my students says: Dr. B’s conspiracy theories. No double-blind peer reviews, no scientific method, no academic prestige to worry about, just my unadulterated thoughts, a hunch. So enjoy:

Why am I fascinated by the turn of the (20th) Century Central and Eastern Europe? I have written about it a couple of times (here and here).

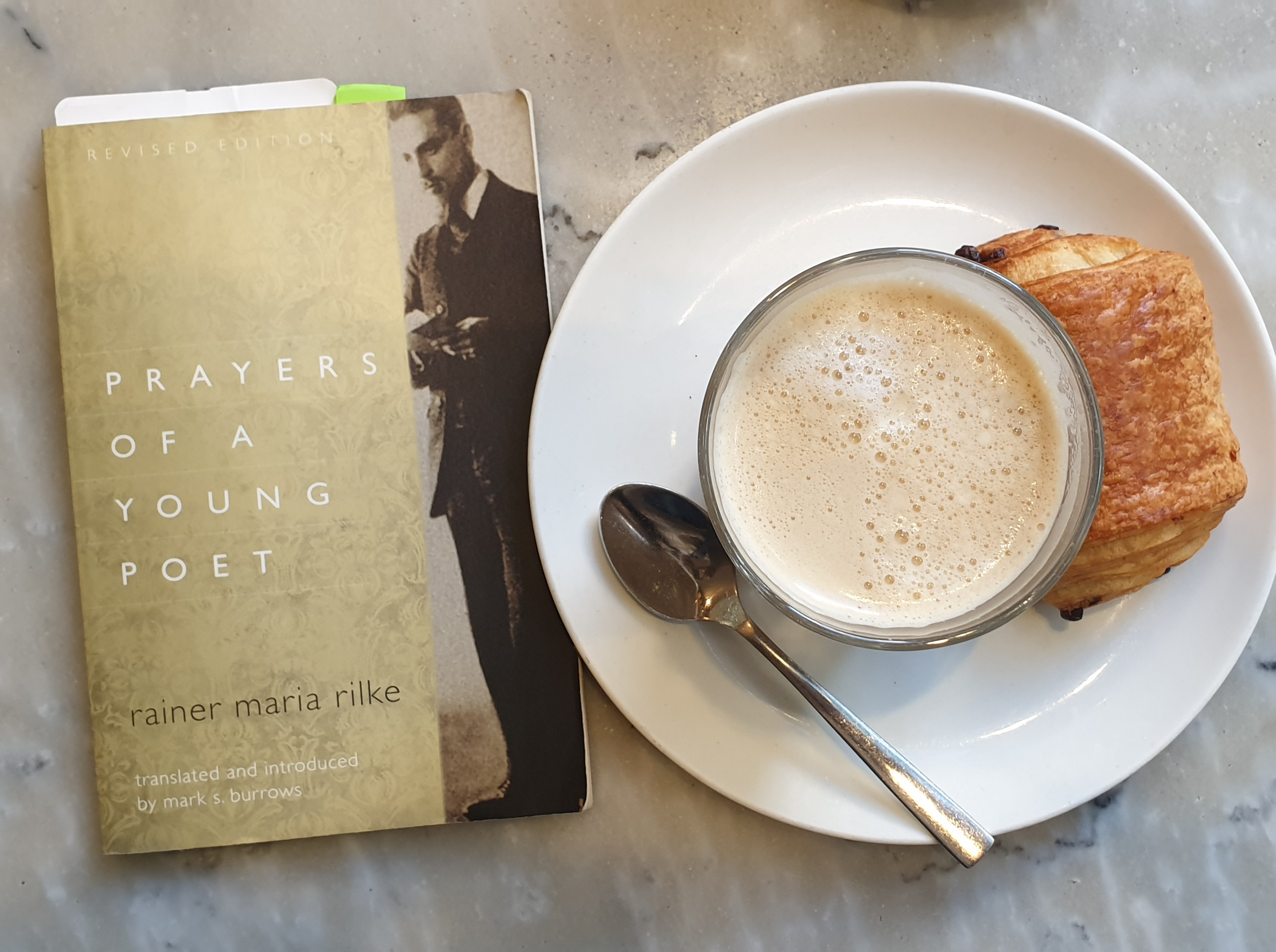

I just finished Rainer Maria Rilke’s Prayers of a Young Poet, and it blew me away!

Rilke authors this 68-poem collection in the voice of a nameless Russian Orthodox monk. The spirituality is palpable. Each poem has a brief footnote denoting where and/or when it was written: “2nd of October, beneath soft evening clouds”, “On the 5th of October, written down in the exhaustion of evening, having returned home after having been out among the people.”

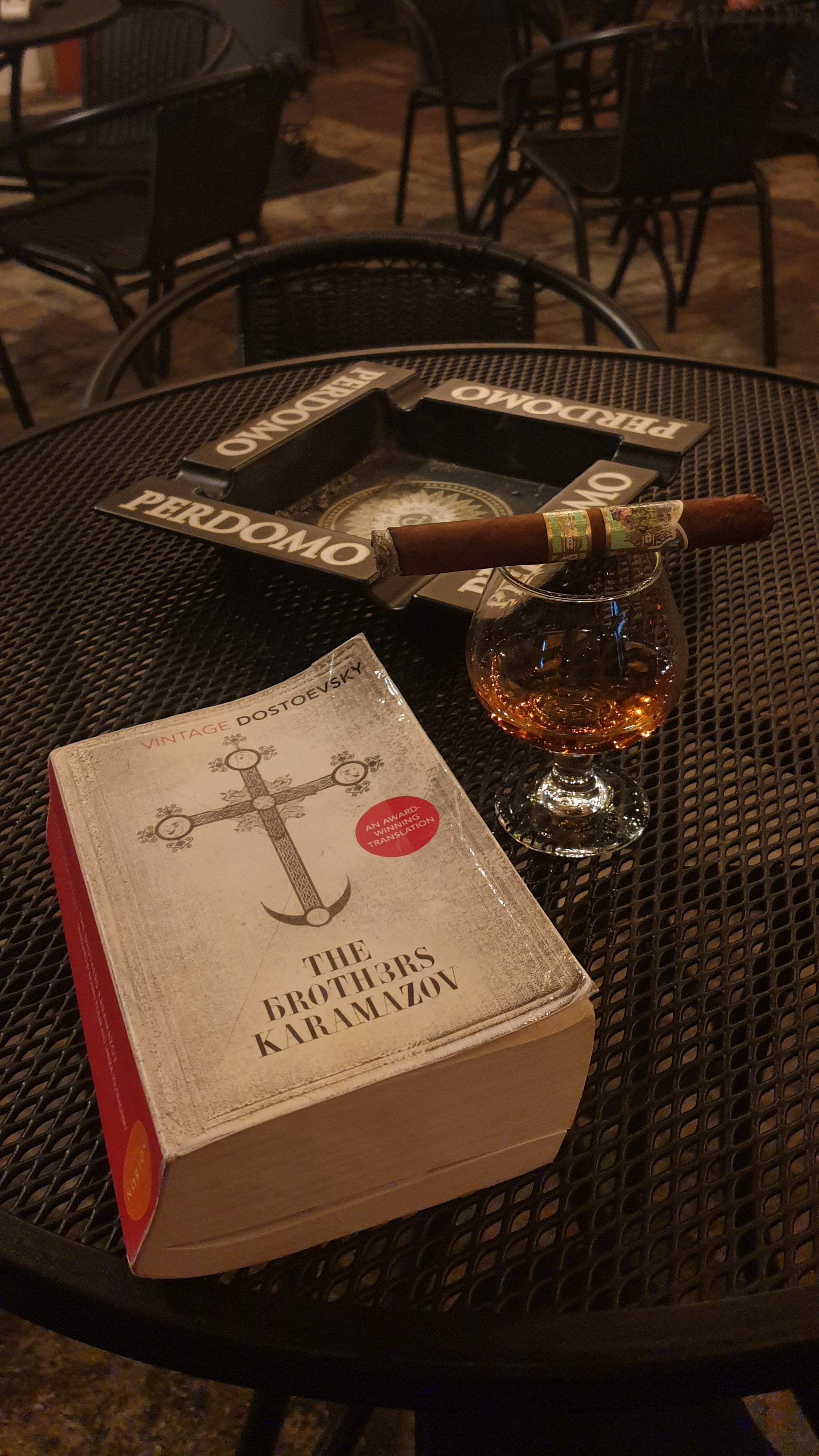

Perhaps due to my ignorance and lack of reading, I kept thinking of Alyosha Karamazov from Dostoyevsky’s novel.

What connects these poems and Alyosha Karamazov is a simple innocence, a pure love of life and humanity in lines like:

“I want to love things in ways no one has yet done.”

or

“The hour bows down and stirs me

with a clear and ringing stroke;

my senses tremble. I feel that I can–

and seize the forming day.”

So, that is my hunch, my thesis. That there is an existential connection between the monk, the narrative author of Prayers of a Young Poet and Alyosha Karamazov, as if he had drafted those poems. But, you say, there are hundreds if not thousands of Russian Orthodox monks and many of them are in literature. My answer to your comment is the first line of this blog post. Also, I am a romantic, can’t you see? And this connection is just beautiful, and delicate, and awesome!

Rilke travelled to Russia and was entranced by their culture, art, and most importantly their rich religious tradition. He also could have read Dostoyevsky’s masterpiece published in 1880, 19 years before the original publication of Prayers in 1899.

Yes, I could go on and on and get all academic, but this is a general interest blog, so there you have it. If you do want me to elaborate on my thoughts, let me know in the comments!!