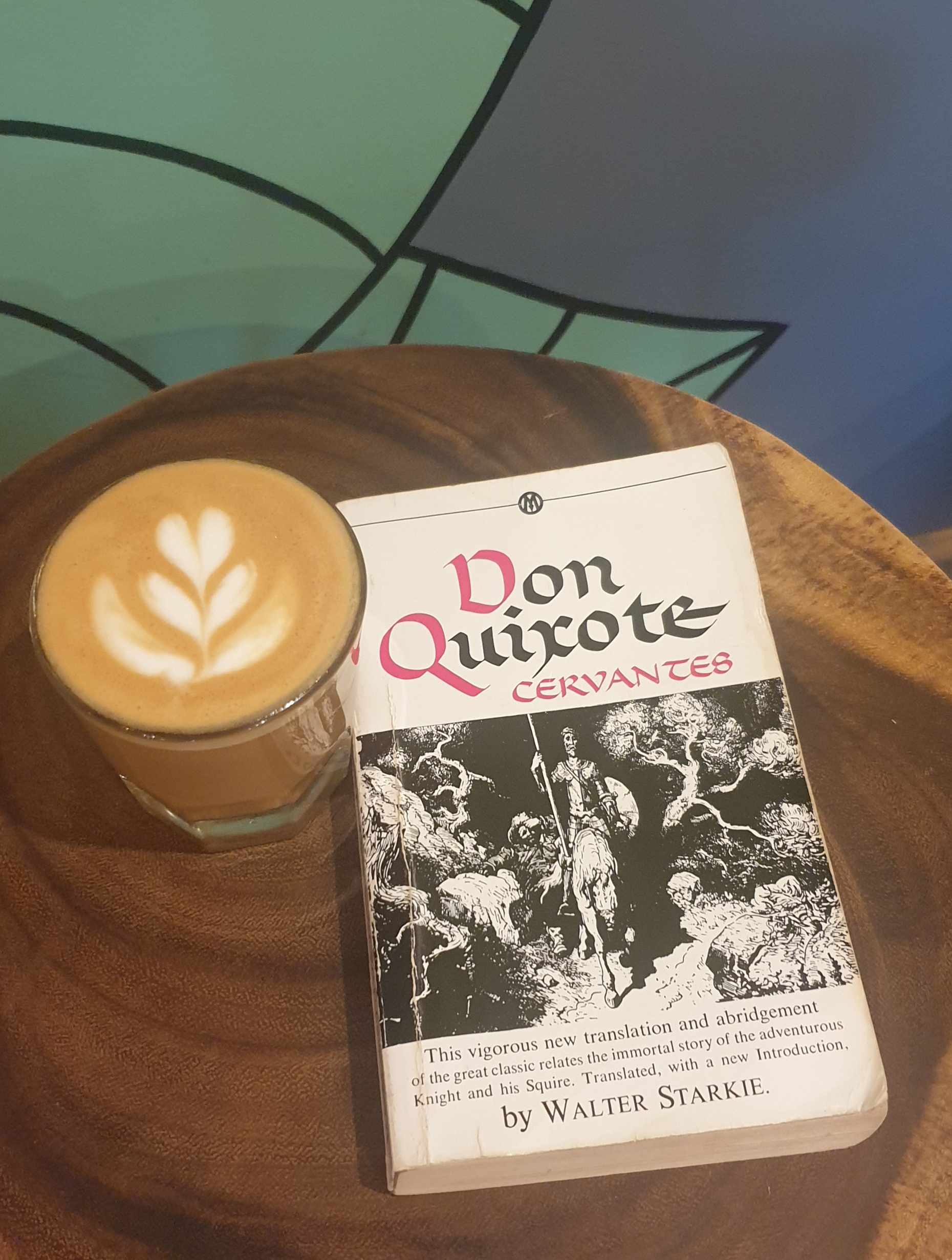

My dad could not stop talking about Walter Starkie. I never gave the fellow much consideration, that was my dad’s thing. My dad even found and bought some of his (many) books. But a few days ago, my aunt passed along a brief bio of Starkie –particularly in his time as Director of the British Institute in Madrid (attached). And I loved it! This fellow did more for Britain than you would think.

Mise en scene: Spain during WWII is a neutral country, at least on paper. After all, Franco won the (in)Civil War in 1939 with help from Hitler and Mussolini. Having said that, when Hitler asked Franco to let him transport his troops and tanks by train to Algeciras (next to British Gibraltar -but that is another story) to get to North Africa, Franco -to his credit- said no. But back to our story.

So, in a neutral but Axis friendly country, in 1940, during WWII, what could Britain do to exert some sort of “soft” power in Spain? The answer: send a phenom of nature, a genius, a virtuoso (literally), a wonder, and let him do his thing. Make sure he looks unassuming, a roly-poly, jolly, violin-playing academic fellow. Give him a fairly vague title like British cultural representative. Finally, give him carte blanche to do as he sees fit, oh and a generous budget, I am sure.

Ironically, Starkie was Irish, from a family of scholars and artists, he graduated from Trinity College in Dublin, with honors in Classics, History and Political Science, oh, and first prize in violin from the Royal Academy of Music in Dublin! After graduating he stayed at Trinity teaching Italian and Spanish. Samuel Beckett was one of his students! During WWI in Italy, he played violin for the British troops and met his wife. Back in England Y.B. Yeats made him director of the Abbey Theatre. From there he was sent to Madrid in 1940.

Starkie soon founded the British Institute – El Instituto Británico, “El British,” where my father, my uncle, and my aforementioned aunt went to school as children of a British Embassy employee (read more about my grandad here). Eventually my sister and I would also go to “El British.” Starkie made the school a center for conferences, concerts, presentations, so forth, which is precisely what Britain wanted in Spain: a cultural beachhead in Nazi friendly Madrid. Not only that, but as a Catholic (remember, Starkie was Irish), Starkie soon made friends with influential Jesuits Heras and Otaño, and eventually with government ministers. In fact, one of Starkie’s biggest victories was to have English as a language option (together with German) in Spanish secondary schools.

On any given day, Starkie could meet with a Spanish government official, play the violin with gypsies, whom he loved and wrote his most famous books about (Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in Hungary and Romania (1933), Spanish Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in Northern Spain (1934), and Don Gypsy: Adventures with a Fiddle in Barbary, Andalusia and La Mancha (1936)), host a conference, write or translate a book -like Don Quijote, and then go home, which served as a safe house for Jewish, Gypsy, and other prosecuted refugees on their way to America.

I asked my uncle what he remembered about Starkie. He told me how the Embassy’s country house was used as a safe house for downed plane crews rescued by the French resistance who were on their way back to the UK to fly again. But to get to this country house one had to drive by a gypsy settlement. Because of the friendship between Starkie and the gypsies, nobody ever dared go near that house to investigate what was going on, why there were cars and vans coming in and out at all times of the day and night, another point for Starkie!

So, besides the eventual victories on the battlefield, Britain scored a major victory in WWII by sending Walter Starkie to Spain.