Clarification: I am not a linguist. I did have to take a linguistics course as part of my PhD coursework, and, of course, it is difficult not to become a linguistics aficionado when studying literature, or when teaching the Spanish language.

Taking advantage of the cultural powerhouse that is Madrid, I recently attended three different lectures (at two different venues) on Spanish linguistics.

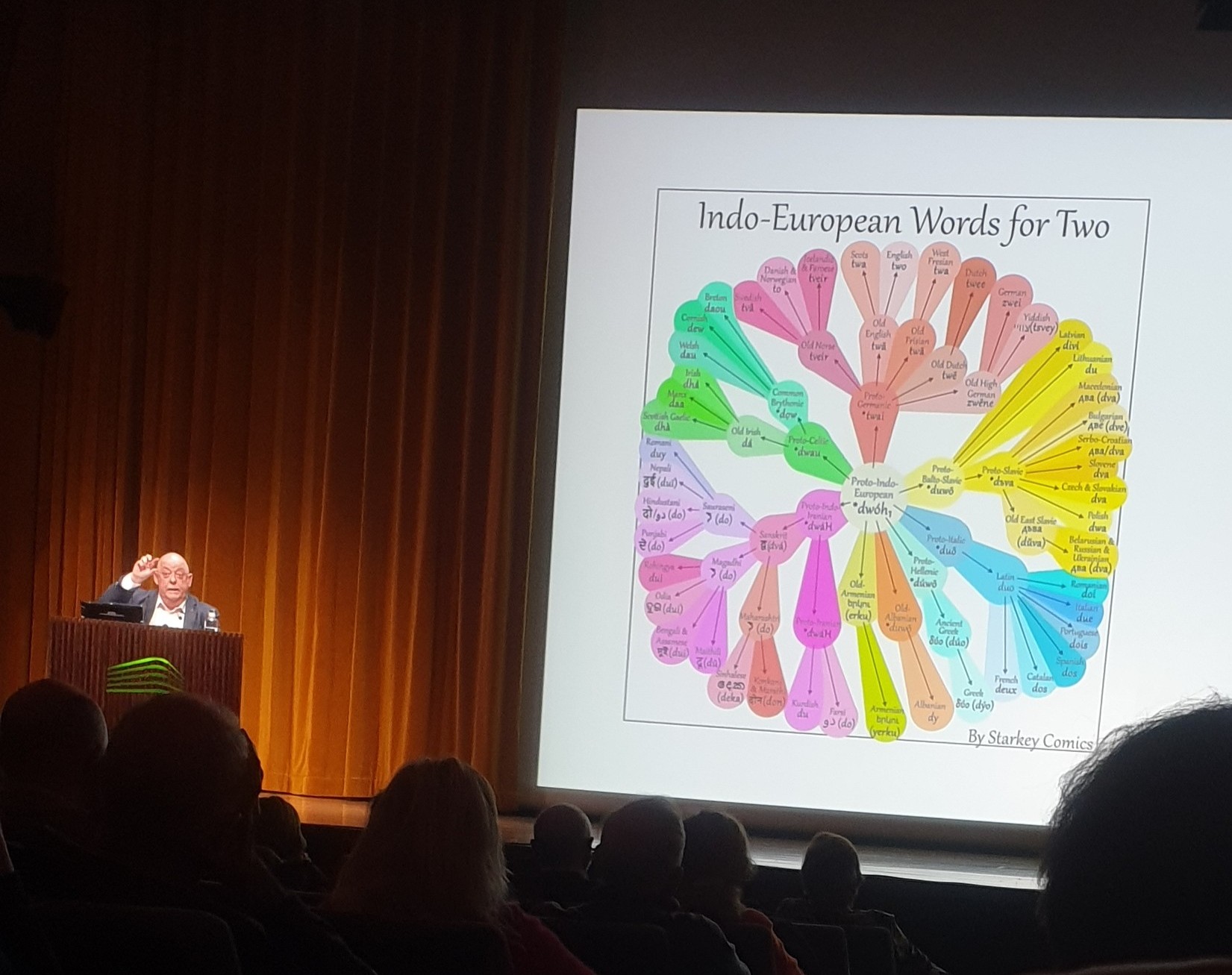

The first one at the Fundación Juan March was a general but excellent introduction to the Indo-European origins of European languages: ¿Qué es el indoeuropeo? La familia de lenguas indoeuropeas, by Complutense University Professor Juan Antonio Álvarez-Pedrosa. In his conference, Álvarez-Pedrosa explained the history of the study of Indo-European languages, dating back to Sir William Jones in 1786, and how he discovered connections between Sanskrit and ancient Greek, the methodology used to track the origins of languages, and how linguists have historically worked. It was a surprisingly enlightening session.

The second lecture in that series, La religion de los indoeuropeos: entre el mito y la historia, was given by Álvarez-Pedrosa’s colleague at the Complutense, Eugenio Luján. Luján explained the collaboration needed between archeologists and linguists to understand the cultures of different ancient tribes, mostly based on Adolphe Pictet’s theory. I did learn that the wheel was used for making ceramics before it was used for transportation! Stuff one learns in lectures on linguistics!

Luján then explained the connection between religion and linguistics based on the three levels of Hierarchy, War, and Production (of children, that is, basically, Love). I did find this section a midge of a stretch, but that is research and academia for you, pushing the envelope.

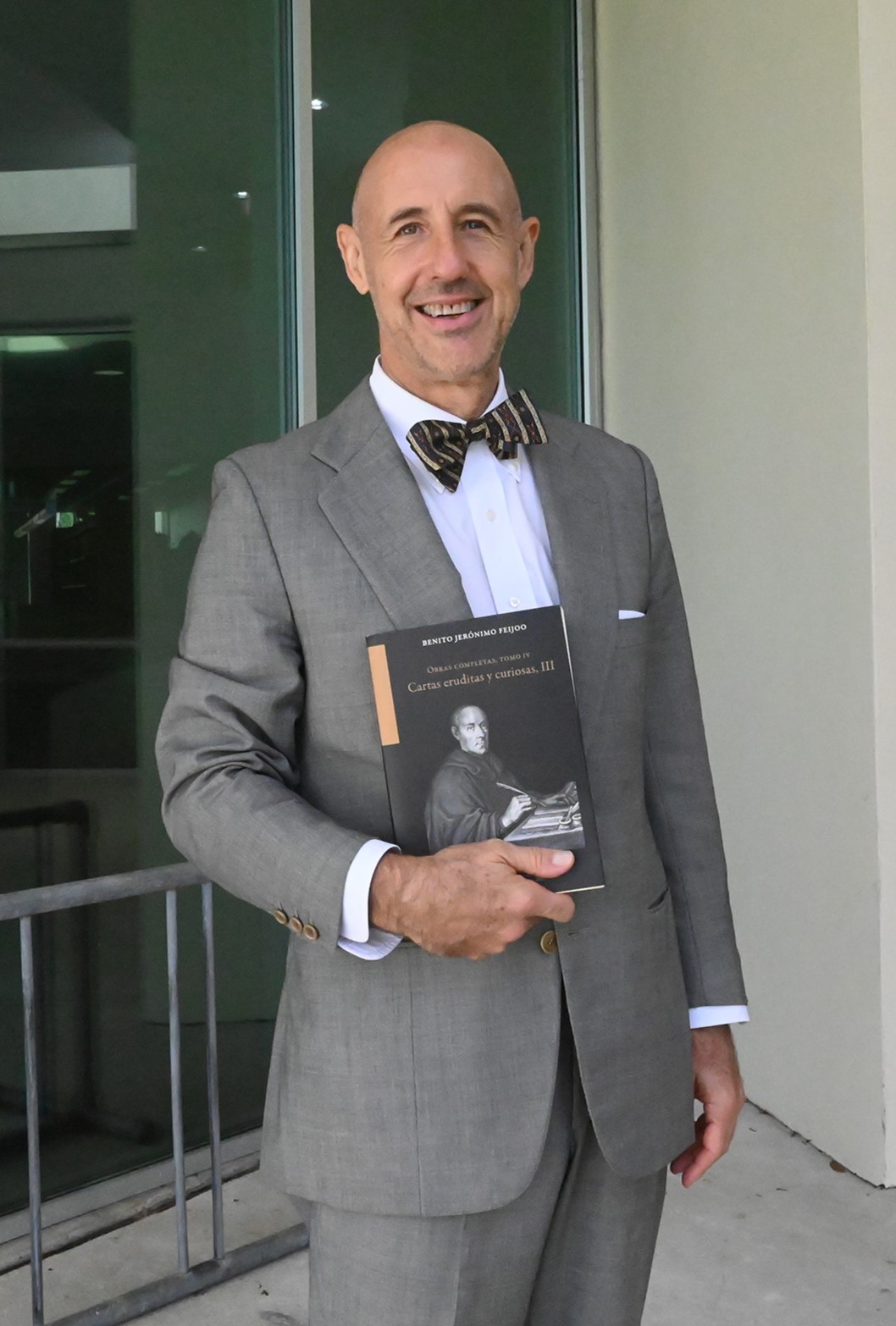

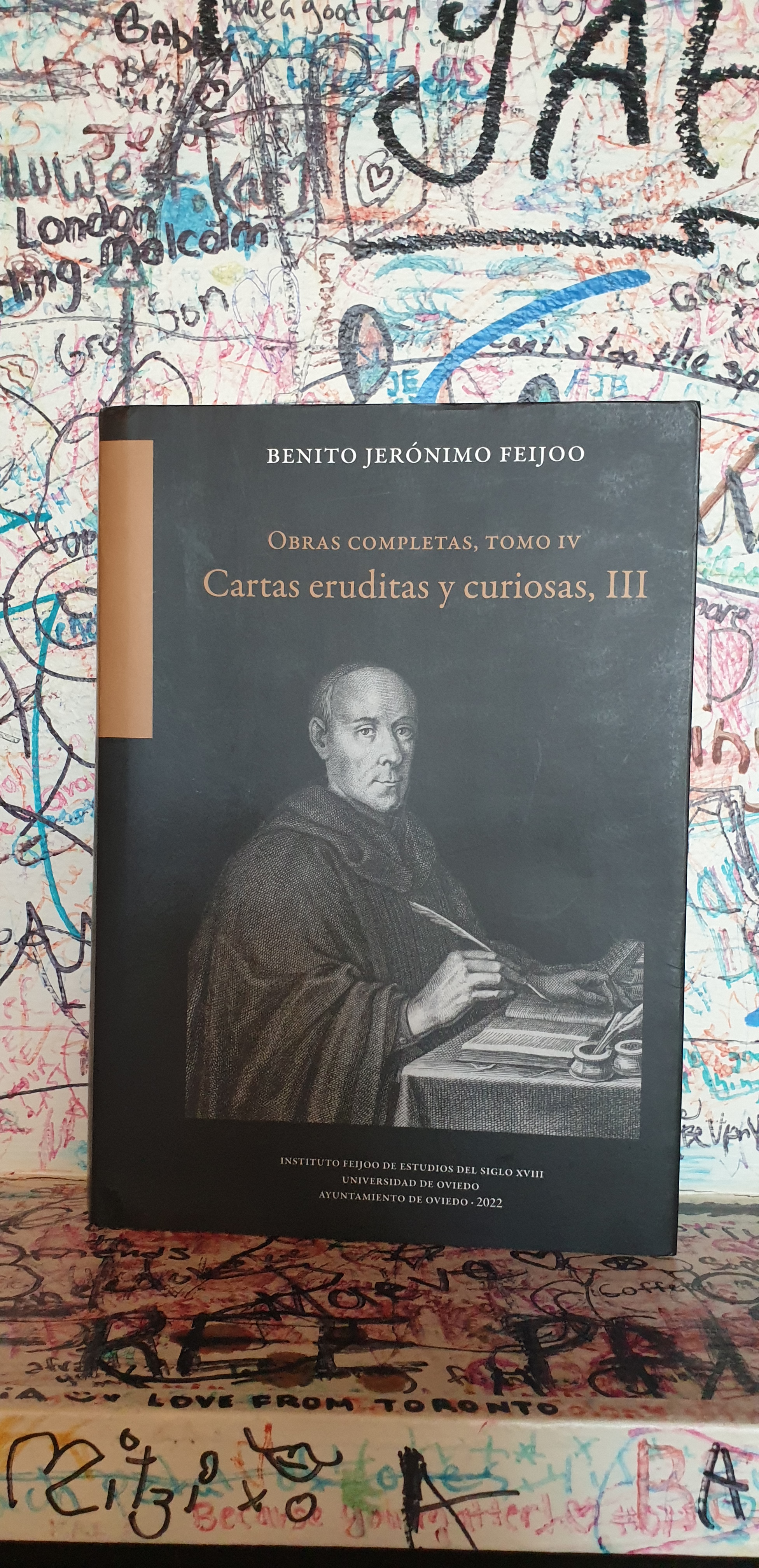

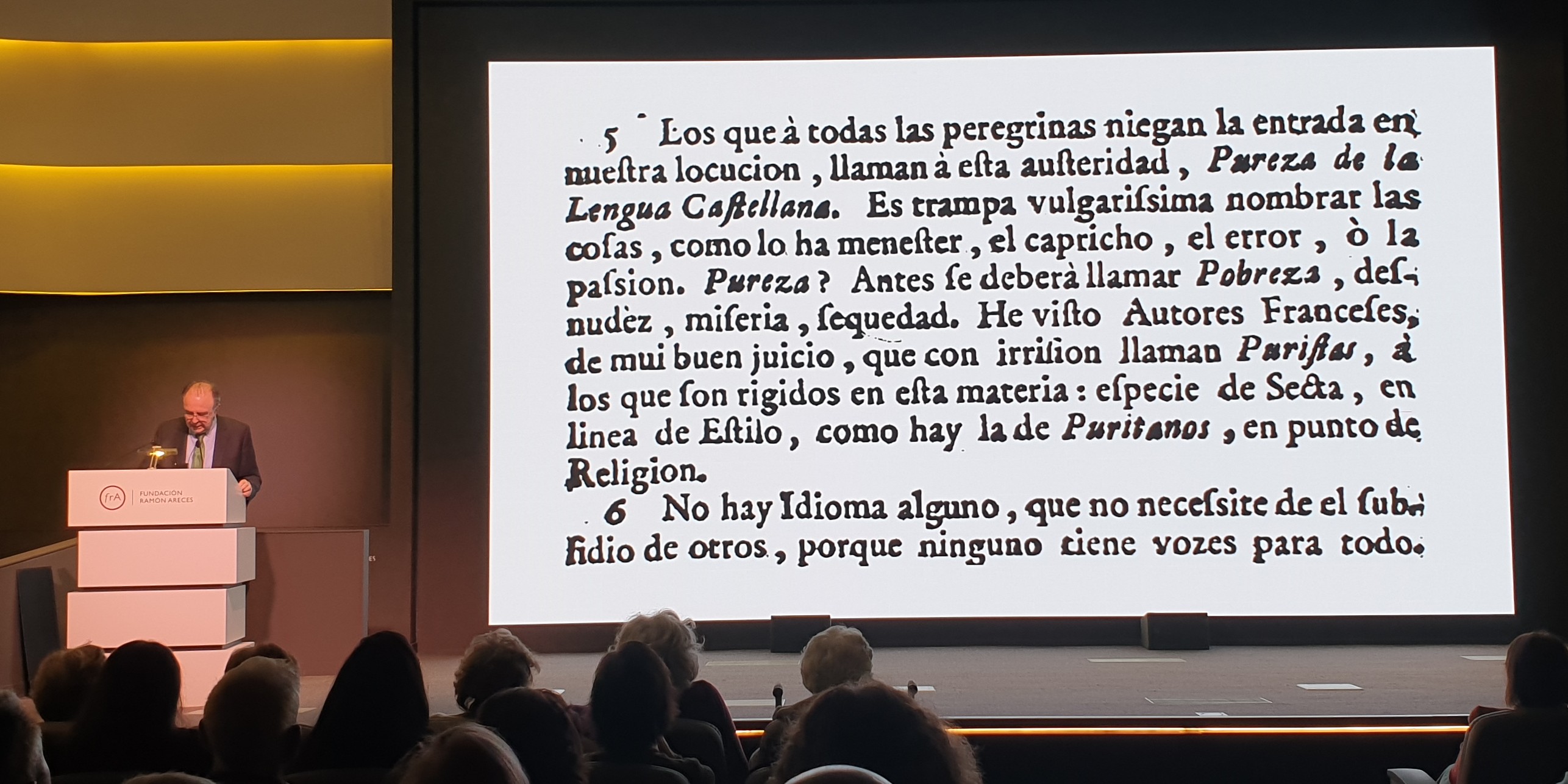

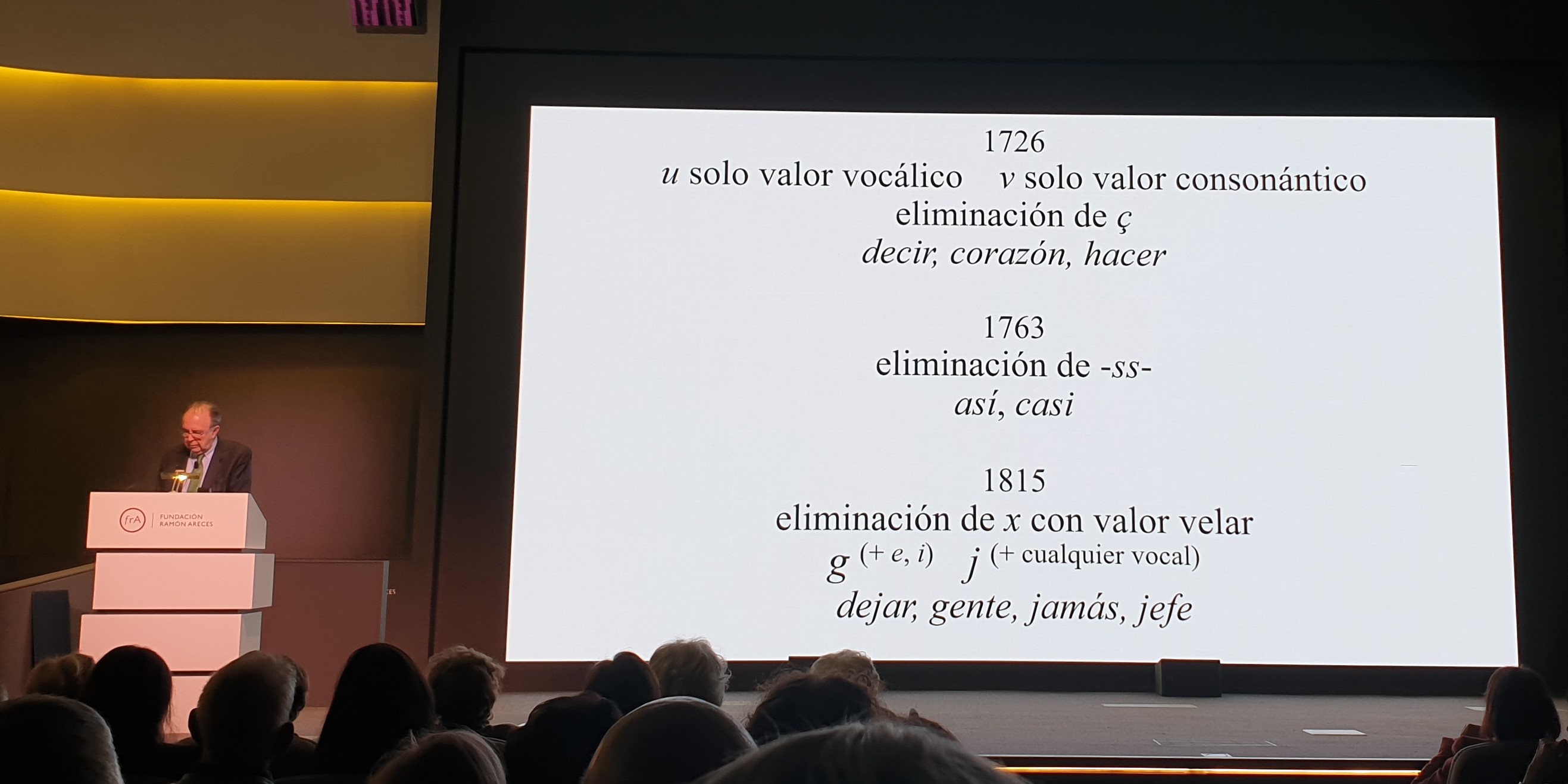

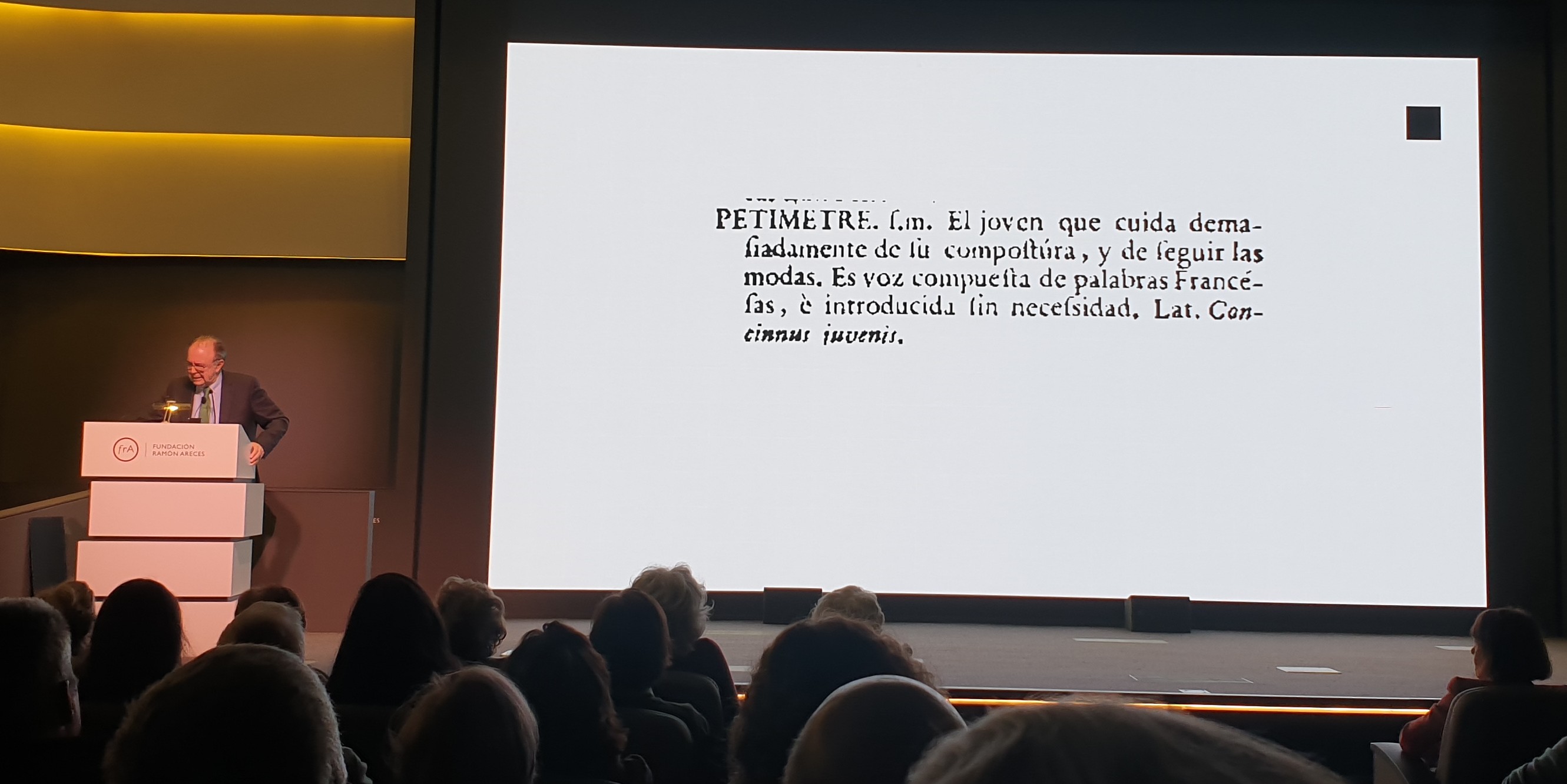

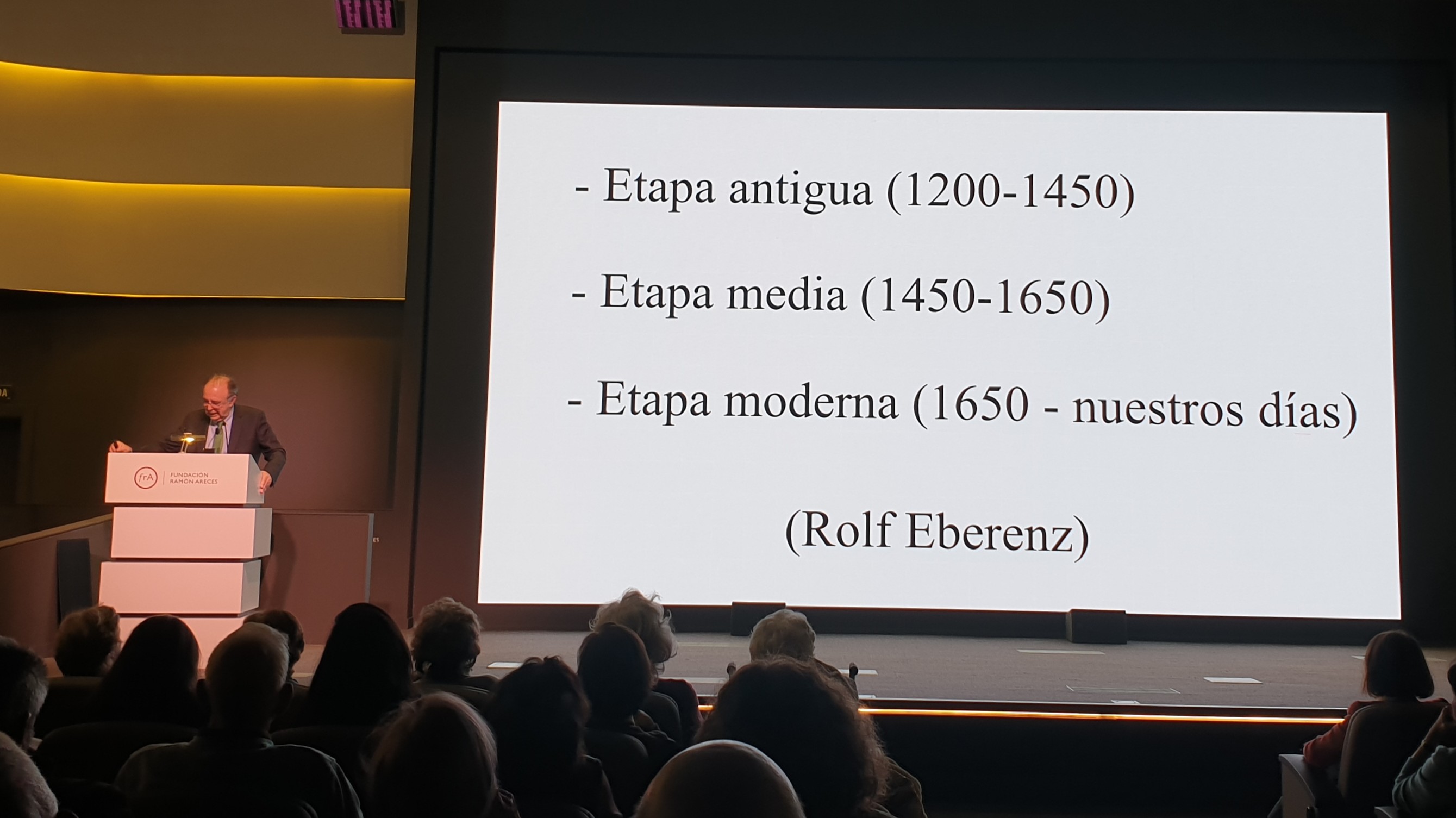

The third lecture was not connected. It was at the Ramón Areces Foundation by Real Academia de la Lengua member Pedro Álvarez de Miranda: Los comienzos del español moderno; el siglo XVIII. This lecture was by far the best! Álvarez de Miranda, with apparently endless knowledge, explained the evolution of the Spanish language in the 18th Century, leading us to “modern” Spanish. He referenced the work of Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Américo Castro, and Rafael Lapesa. He also explained the important work of the Jesuits and the missionaries in America, the novatores who were scientists in early 18th-century Spain, and, of course, the work of Benito Jerónimo Feijoo and of the Academy of which he is a member.

All in all, a great trio of lectures. Let me know in the comments if you have any questions.