One of the most popular posts on this blog is Don Quixote’s Influence on Existentialist Philosophy, which is a bit embarrassing because it is not very good. I wrote it very early on in my master’s, and while the idea, the thesis is good, I did not develop it very deeply nor fully. It is mostly my gut feeling, my intuition that comes through.

I have thought and thought about this since 2008, and more importantly, I have read a lot that I would not have had the time to read for that little essay. I have read more Dostoyevsky, Sartre, Kierkegaard, El Quijote desde Rusia with three brilliant essays by Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, and Merejkowsky, more Unamuno, Graham Greene, and on and on.

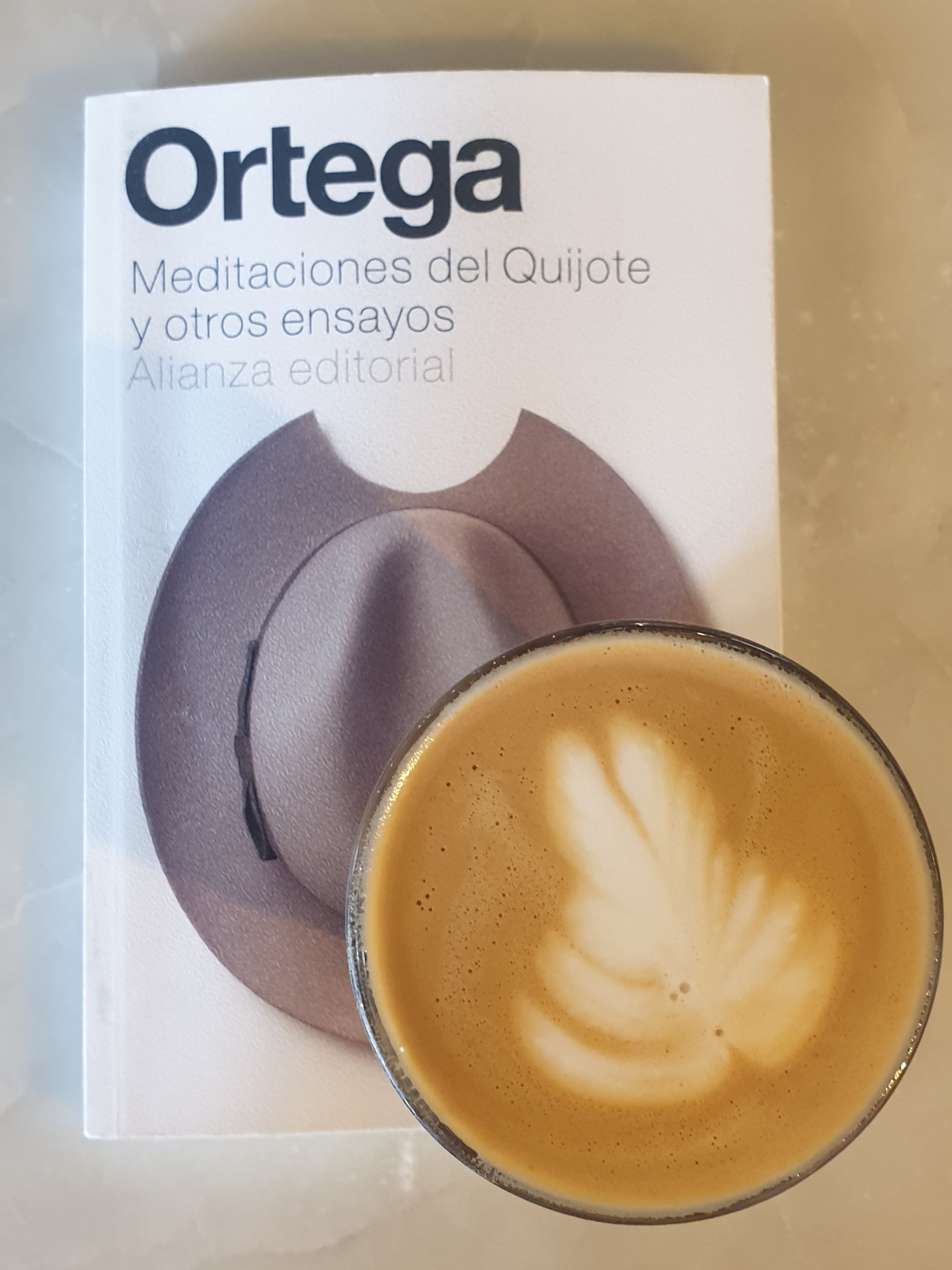

For Christmas, Celia gave me José Ortega y Gasset’s Meditaciones del Quijote y otros ensayos, which I had wanted to read for years.

All this reading confirms the theory that Cervantes crystallizes the thoughts of the preceeding centuries, from the ancient Greeks on Liberty to the early Christians on Free Will, where the Self is swimming in the primordial waters of philosophy, floating around until Cervantes’ electric genius gave abiogenesis form to Don Quixote, consciously creating his fortune, bringing about the concept of existentialism. The textbook example of this is the beginning of chapter VIII. Read it carefully, what does Quijote see? He sees them. What are they? Windmills or giants…

Don Quixote is the proverbial Tetrapod fish walking onto earth. It will be up to Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, Unamuno, and Ortega before Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre finally come up with the label that puts a nice bow on the Darwinian evolution of thought that delivers Existentialist theory.

Meditaciones has the famous quote “yo soy yo y mi circunstancia, y si no la salvo a ella no me salvo yo”. So, yes, you are responsible for what you do in life, with life, but you also must deal with the circumstances surrounding your life. But Meditaciones is not what you expect. It is not a direct essay on Ortega’s thoughts on El Quijote -although it is also that- it is that in a meandering, roundabout way. Ortega talks about the Mediterranean culture, compares it to the Germanic culture as he lived in Germany for many years. This is evident when he quotes Nietzsche’s “Live dangerously”, which is, of course, the whole premise of Quijote’s adventures.

As a good philosopher, questioning El Quijote, Ortega ends up asking more questions than answering them. One key observation comes when he compares Cervantes to Shakespeare, something commonly done, as they were, after all, contemporaries. And here is the difference: Shakespeare explains himself, Cervantes not so much. Some of that difference might be due to the difference in genres: Theatre vs the modern novel, but nonetheless, there it is. Another common assumption is the Spanishness of Quijote, which leads Ortega to call Spain the “spiritual promontory of Europe”.

Another of Ortega’s brilliant observations, connections are between two Baroque masterpieces: Quijote and Velazquez’s Meninas, how we can step into each work and see it from the inside. This imaginary stepping into these makes them realistic. That realism is what makes us, and understanding ourselves in that work, that singularity, is what makes us heroes, a full hymn to Existentialism!

So what I wrote 17 years ago, although not the most brilliant, not the best written academic paper, still stands. Cervantes, by creating Don Quijote, is setting the cornerstone of Existentialist philosophy.

Don Quixote’s influence on Existentialist Philosophy Part II – José Ortega y Gasset

I see it differently:

not knowing that Cervantes did not write the Don Quixote; he was just a figurehead. Francis Bacon invented the “History of the Don Quixote and the valorous wittie Knight-Errant Don-Quixote of the Mancha”. This masterwork was written with other authors: Ben Jonson took the part of Sancho Panza. John Donne ( ps called himself often Jack Donne ( this sounds better, his name is only in the DQ, not in the Avellaneda and his secret name is don Diego de Miranda) had to write the poems. ‘The two friends” Francis Beaumont ( ps. Antonio de Bracamonte) & John Fletcher ( secret name mosén Valentín), they were assigned the task to write the loose stories.

Or do you really think Cervantes had an old-greek study? A Latin education? A philosophical background, studied at an university..

Oh well, actually I say it too pushy: the don quixote is a book that is for everyone. and then depending on your mental development. One sees it as entertainment, the other as study and the other as the esoteric way.

Shakespeare, like Achilles and Hector, frolics in the midst of the heroic struggle for human greatness. Cervantes sits next to Apollo, Aphrodite and Heracles and looks from the heights of Olympus with a faint smile at the unfortunate efforts of poor mortals.

We have the feeling that the Briton is ready to endure without hesitation the difficulties and sufferings of existence. The Spaniard has given up the fight with resignation, the struggle of life has become too hard for him.

You understand that Rüegg didn’t know that Shakespeare and Cervantes were just figureheads.. so change the names into Bacon.

DQII has 74 chapters. Only the first chapter has an ornated initial. The foreword also has such a decorated initial letter. ‘Now God defend!’ If I could get that N.. and add this first letter .. then I get the following row: 75 capital letters divided by 5 is 15 letters.

NCTDS TWTBM TDDTA DDTDD SATIT DHCWD VGDWG WTTAA CITWT OWTTW CTCTT STNWT TTDGT DAITT STDCA

I think all the letters W must be understood as the Greek omega: in other words are equivalent to vowels and thus be translated into a B. Once I have to adjust my theory: the -O- may be a vowel that only occurs once, but in front of it there cannot be a -B- twice in Bacon’s binary code. This -O- must therefore become an – A– the opposite of the Omega. If I try to catch these 15 letters in a sentence, it says:

I BACAN CALL V BACK

Bacan is there instead of Bacon. Now this means that this word is phonetic in this context, just like the letter V or U = you, which you also have to read phonetically.

The V is used as a pun for -you-. This -V- abbreviation was first used as a replacement for -you- by Shakespeare, read F.B., in the comedy ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’ in 1594/95.

Have a nice day, Jettie H. van den Boom

LikeLike

Pingback: The Quixotic in David Lynch’s The Straight Story | Antonioyrocinante's Blog